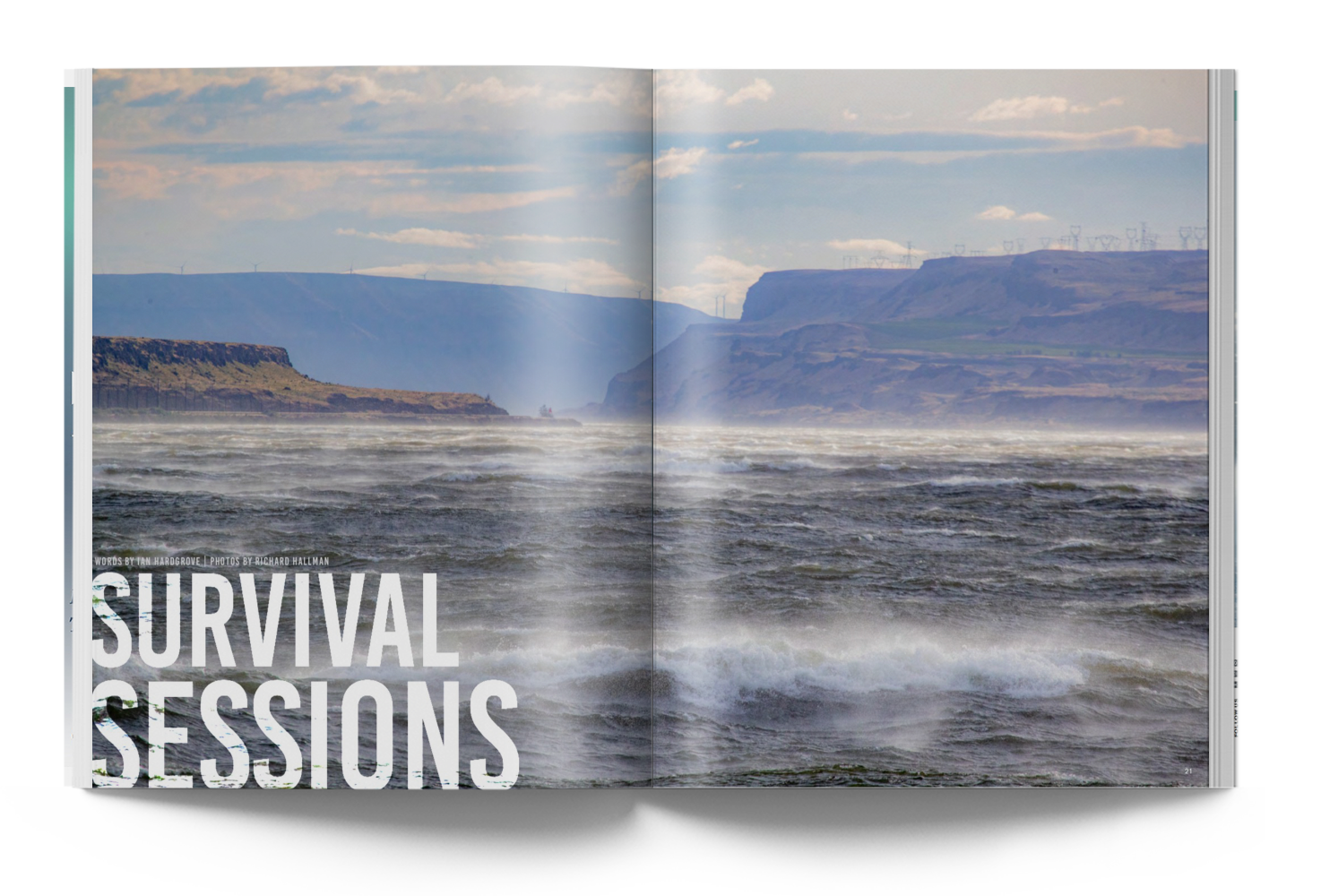

Professional photographer Richard Hallman stepped out of a darkened convenience store into a savage wind tearing through the empty streets of Biggs, Oregon, a one-horse town 40 minutes east of Hood River. With leaves and debris whipped into the frenzy of hurricane caliber winds, the massive low-pressure system presiding over the Columbia River Gorge had damaged the electrical grid, shuttering the lights and businesses of small towns dotted along its shores. The situation escalated as Richard and Vetea Boersma walked toward their vehicle and watched a 30-foot section of roof peel off a motel across the street. Leaving Biggs’ single, now non-functioning traffic light behind, Richard turned his van to the east and watched out of the corner of his eye as aerosolized water blew off the tops of the Columbia’s rolling swells and kept pace with the speed of the van the speedometer pegged around 70mph. Despite the ferocity of the jumbled-up storm

winds funneling eastward through the Columbia River Gorge, Vetea studied the thundering river in anticipation of a groundbreaking session.

The forecast for May 30, 2020, was on track to record wind speeds rarely seen on the network of sensors lining the Hood River corridor.

As a 27-year veteran of life in the Gorge, Richard has spent the bulk of his adult life witnessing the cold air of Portland accelerating towards the warmer basin east of the Cascade Mountains as it creates a venturi-influenced wind tunnel of unparalleled strength. Yet the forecast for May 30, 2020, was on track to record wind speeds rarely seen on the network of sensors lining the Hood River corridor. A low-pressure storm was forecasted to produce winds averaging 50mph with gusts to 70mph, accompanied by heavy rain and thunderstorms that showed promise of tapering into clearer skies towards the late afternoon… To read the rest of Survival Sessions subscribe to Tkb Magazine.